Bread, circuses, and Oscar buzz

Thursday | November 6, 2014 open printable version

open printable version

Kristin here:

A little over a month ago, Entertainment Weekly posted a story about this year’s Oscar bait. It began in a surprising way:

It’s September, so why wouldn’t we start predicting an Oscar race that won’t finish for another five months?

To be fair, Venice, Telluride, and the Toronto film festivals have all concluded. Many films have screened. Many films have connected with audiences, and a rough draft of the Oscar race is beginning to come into focus. Sure, no Academy member will even begin popping in those screener DVDs for another couple of months, but it’s still worth discussing what has buzz and what is likely to still be on voters’ minds once the weather finally begins to cool off.

Here’s a very early look at what the race looks like now.

This wouldn’t have been surprising in a comparable story, say, five years ago. But in the last few years we have somehow gotten into a nearly half-year-long cycle of what is now invariably called “Oscar Buzz.” Why does Entertainment Weekly need to justify printing such speculation in September when every other remotely entertainment-related venue is already doing it?

Just as David and I avoid printing ten-best lists at the end of the year (apart from our surprisingly popular series on ten-best films of 90 years ago), so we avoid speculating on Oscars, Golden Globes, BAFTA, or Toronto awards. It’s hard, however, to avoid seeing this kind of speculation when it’s all over the internet and fills the pages of trade journals like Variety and The Hollywood Reporter.

This increasingly obsessive coverage isn’t merely annoying. It has significant consequences. One egregious effect has gotten more common over the past two or three years: a new tendency to treat film festival programming as indicating what might be nominated for big awards. Now journalists routinely treat big festivals as competing with each other, not for the most intriguing films but for the big award bait.

Maybe some festivals do compete in this way, but the coverage is certainly encouraging such behavior. Still, these festivals also show a lot of other films–more obscure ones that might be more interesting and which the public should know about. The more “Oscar buzz,” however, the less attention paid to smaller films.

David and I tend to think of festivals as an alternative distribution and exhibition circuit. That circuit makes available films that won’t come to your local multiplex, or even your local arthouse. Those of us who are devoted to movies of a wide range of types go to festivals to catch up on world cinema, as opera devotees travel to cities that have opera houses and festivals. But there are signs that some festivals are starting to cater to the glitz of awards-friendly films and red-carpet events, and we fear that others may follow suit.

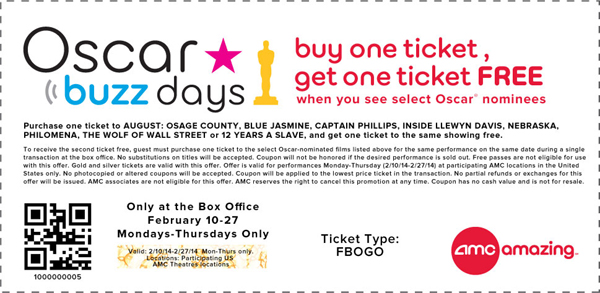

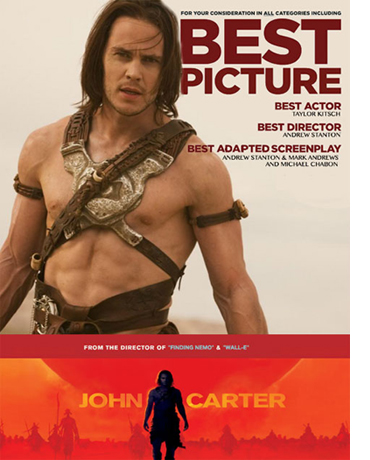

For your expensive consideration

Oscar buzz is great for the trade journals. Even those who don’t subscribe to them know about the “For your consideration” ads that pop up, glossy and  usually covering a full page of the large-format Variety and Hollywood Reporter–sometimes a two-page spread. These ads used to come out mainly before the Oscar nominations were being voted on, but now the season has expanded, and any vote-based awards show provides occasion to run them. A new practice is to run additional magazine ads in the weeks after the awards shows as well, congratulating the winners. Such ads used to be mainly taken out by the production studio and/or distributor, but now talent agencies, professional guilds, and other organizations will run such ads, listing all their clients, members, and employees who have been nominated or have won awards.

usually covering a full page of the large-format Variety and Hollywood Reporter–sometimes a two-page spread. These ads used to come out mainly before the Oscar nominations were being voted on, but now the season has expanded, and any vote-based awards show provides occasion to run them. A new practice is to run additional magazine ads in the weeks after the awards shows as well, congratulating the winners. Such ads used to be mainly taken out by the production studio and/or distributor, but now talent agencies, professional guilds, and other organizations will run such ads, listing all their clients, members, and employees who have been nominated or have won awards.

Of course, awards-related ads generate revenue for print magazines in a time when the internet is luring away readers. Part of the expansion of “for your consideration” ads has been promoted by the journals themselves. If they publicize more films as potential Oscar nominees, the studios will want to, or at least feel pressured to take out ads for films that they might not otherwise think were plausible nominees. They also have to keep their talent happy. If a star gets a lot of Oscar buzz in the media, he or she might begin to expect the studio to run such ads, whether or not the buzz is based on any real likelihood of a nomination.

Oscar buzz is also great for filling of column inches or composition panes with text that costs very little to generate. Reviewers have to be sent to festivals so they can see the latest films, and they go armed with expense accounts. As long as they’re there, why not have them write about Oscar buzz as well? They’ve already seen the films, written their reviews, and perhaps interviewed some of the talent. Writing about Oscar buzz is easy and based on chitchat and speculation. It’s presumably a lot cheaper to run such stories than to have a reporter spending a lot of time tracking down information for a hard-news item about business trends in the industry.

It’s also easy, since if a writer is just speculating, he or she can’t be wrong. Nobody will go back after the Oscars and blame an author for not having predicted a nominee correctly. If most of the infotainment press had predicted the wrong winner, they can generate drama by writing about a “surprise” winner to make up for it. And since a consensus often quickly develops among reviewers and commentators about who will be nominated, a lot of people are making pretty much the same predictions anyway. If they’re wrong, they won’t be the only ones.

Another advantage that Oscar buzz offers film reviewers has occurred to me. It’s a minor but pretty pervasive one. Acting is a hard thing to describe, beyond making some sort of enthusiastic remark about someone being superb in a role or an actress totally losing herself in a part. But if you just say, “Steve Carell generates Oscar buzz for his role in Foxcatcher,” you’ve given it the highest form of praise and haven’t had to describe it. The same thing can be done with directing, design, cinematography, and musical scores.

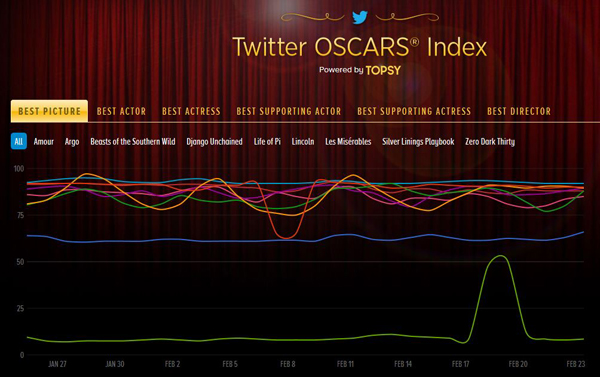

The buzz spreads

Oscar buzz doesn’t just pervade trade-press coverage, fan sites, and infotainment media. The same buzz ripples out through all levels of publication, and that’s true of the coverage of festivals as early indicators of award-worthiness. Online sites are scrambling at all times to draw attention, and anyone can speculate about what might get nominated and win, even if they don’t go to the big “buzz” festivals. The public seems to have an endless appetite for this stuff.

People Magazine, which did send at least one reporter to Toronto, posted a story entitled “All the Oscar Buzz (Reese! Eddie! Jen?) from Toronto.” The author is pretty straightforward about her interest in the movies she saw: “The second half of the festival delivered big-time, adding powerhouse performances and major A-list Oscar buzz to the mix. Here’s some of what we discovered … start planning your fall moviegoing and Oscar pools now!”

Even National Public Radio, which does run more serious stories on cinema, broadcast an interview with critic Bob Mondello and blogger Linda Holmes, called “Oscar Buzz Builds at Toronto.” Reporter Robert Siegel, who was not himself at the festival, knew from previous buzz just what questions he should ask, as with this: “Now, the Toronto Film Festival is one place where Oscar buzz begins for actors. Let’s talk about a few performances. First, Steve Carell in the movie Foxcatcher.” One might imagine asking instead, “Toronto is a place where new talent is discovered. Have you seen any foreign films or intriguing American indies with amazing performances by unknowns?” But that would not be, as People would say, “major A-list Oscar buzz.”

I mentioned that the buzz is more than just annoying and distracting. One has to wonder if such relentless speculation becomes self-fulfilling. After all, people in the film industry read the trade papers and the popular press. In the case of the Oscars, it’s industry professionals who do the nominating. For the Golden Globes, it’s a small number of entertainment-press people, and they are self-evidently aware of what’s being buzzed about. Despite all the talk of diversity in filmmaking being made possible by digital technology and the rise of indie distribution options, the coverage in mainstream journals doesn’t deal much with non-mainstream efforts. Among all this buzz, there is some speculation about nominees for the foreign-language category, but that, too, tends to involve familiar names. If Asghar Farhadi has a new film out, it will inevitably be mentioned in Oscar buzz, but would an equally good Iranian film by a newcomer get the same attention? Maybe from a few reporters, but not with the uniformity of opinion with which the prominent films are treated.

To most readers, however, the foreign-language category is of minor concern, and Oscar buzz is largely confined to big Hollywood releases and the most prominent of independent films. At best, indies are included as “other possibilities” in prediction lists. Ann Thompson, for example, divides her “Oscar Predictions 2015 Update” lists into three categories: “Frontrunners,” “Contenders,” and “Long Shots.” I guess the idea now is that just to be nearly nominated for an Oscar is honor enough for a worthy film that is realistically speaking not Oscar bait. Am I being too cynical in thinking that it’s also a way to include more possible names and hence increase one’s chances of being right about some?

Premieres and galas

Indiscriminate Oscar buzz is pretty familiar by now. But during the last year or two another notion has emerged. There’s a push to define big film festivals most importantly by the fact that they spotlight awards-worthy films. These festivals are said to be competing, not for good films, but for titles that will capture award nominations.

Justin Chang has recently traced how the stress on Oscar-buzz titles arose within the festival community. In his late-August article, “Telluride vs. Toronto: The Battle for Oscar Supremacy,” Chang points to the shifting policies of the big festivals. This year Toronto instituted a new policy: only films making their world or North American premieres would be screened during the first four days of the festival. This tactic sought to counter Telluride’s advantage of taking place shortly before Toronto. (This year Telluride ran August 20 to September 1, Toronto September 4 to 14.) The new policy apparently arose from the fact that in previous years Telluride, despite running far fewer films than Toronto shows, had managed to screen more Oscar-winning titles.

Festivals have always competed for major films and for premieres, and whether Toronto’s change of policy was directly tied specifically to the Oscars may be up for debate. It might instead be that the press perceives it that way because of commentators’ new emphasis on festivals as Oscar predictors. Perhaps it’s a little of both. Clearly, however, journalists now perceive this competition as hot subject matter for Oscar buzz. Scott Feinberg entitled one article on Telluride for The Hollywood Reporter, “Telluride: Benedict Cumberbatch Leads Weinstein’s ‘Imitation Game’ into Oscar Fray.” Variety’s Tim Gray, whose official title is “Awards Editor,” also reported from Telluride: “Reese Witherspoon’s ‘Wild’ Premieres to Oscar Buzz in Telluride.” An article on CinemaBlend bears the forthright title, “Benedict Cumberbatch, The Imitation Game Win The Telluride Battle for Oscar Buzz.” This sort of coverage pressures the festivals to move further in this direction. Who wants their festival to be reported as having lost the battle for Oscar Buzz?

Festivals have always competed for major films and for premieres, and whether Toronto’s change of policy was directly tied specifically to the Oscars may be up for debate. It might instead be that the press perceives it that way because of commentators’ new emphasis on festivals as Oscar predictors. Perhaps it’s a little of both. Clearly, however, journalists now perceive this competition as hot subject matter for Oscar buzz. Scott Feinberg entitled one article on Telluride for The Hollywood Reporter, “Telluride: Benedict Cumberbatch Leads Weinstein’s ‘Imitation Game’ into Oscar Fray.” Variety’s Tim Gray, whose official title is “Awards Editor,” also reported from Telluride: “Reese Witherspoon’s ‘Wild’ Premieres to Oscar Buzz in Telluride.” An article on CinemaBlend bears the forthright title, “Benedict Cumberbatch, The Imitation Game Win The Telluride Battle for Oscar Buzz.” This sort of coverage pressures the festivals to move further in this direction. Who wants their festival to be reported as having lost the battle for Oscar Buzz?

As Toronto already has been. The website Sight on Sound has a regular column, “The Hype Cycle,” which runs during “awards season” and has a daily summary of awards speculation. In one entry, “Toronto, Telluride and Venice Oscar Buzz (Part 1),” we read:

The Toronto International Film Festival’s People’s Choice Award has been one of the most reliable barometers for both Best Picture contenders and winners, having recently recognized Slumdog Millionaire, The King’s Speech, Silver Linings Playbook, Precious and 12 Years a Slave.

This year however, Toronto may have gotten the short end of the stick compared to its contemporaries in Telluride, Venice and the upcoming New York Film Festival. And it remains to be seen whether any of these titles can make for a plausible, formidable or least of all permanent frontrunner. Let’s take a look at this week’s rankings.

In sum, coverage of Oscar buzz is easy to generate. Trade journals like Variety and The Hollywood Reporter, however, are becoming a lot less useful to industry professionals and to film enthusiasts when they devote so much space to the same sort of speculation going on in the popular press. These journals’ subscriptions are costly, and yet between the awards coverage and the articles on expensive real estate, restaurants, and fashions, they contain far less solid industry news than they used to. In the long run, is this approach beneficial to readers and the journals themselves?

Still, there is a benefit to the festivals to have at least a few high-profile films which potentially could be nominated for awards. For one thing, simple box-office. Festivals depend on ticket sales for part of their income, and the more obscure fare doesn’t bring in as many customers as those high-profile ones.

Beyond that there are the patrons. Big donors like the glamor of red-carpet events. At the parties after the major screenings, they get to schmooze with the famous and talented. Companies that act as sponsors like to have their brand associated with prestigious films–and no doubt their officials also like to schmooze with stars. The big films get prime treatment (evening slots, biggest auditoriums, opening and closing galas), even though those same films, like Wild and Foxcatcher, are often the ones soon to be released theatrically.

Most festivals have far more films in their programs than the few high-profile ones, and most programmers do attempt to show a wide range of films, including documentaries, local films and foreign films unlikely to be picked up for wide distribution. To stress the competition for few buzzy films and ignore the rest does a disservice to us all.

One other effect of linking of Oscars to the big festivals of the early autumn is to further disadvantage good films released earlier in the year. Commentators have long lamented the fact that potential Oscar nominees released early tend to be forgotten by the time the nominations are made. There are occasional exceptions, with The Silence of the Lambs (released in February, 1991) being the usual example cited. Variety‘s Tim Gray recently speculated on whether Academy members will keep The Grand Budapest Hotel and Boyhood in mind when making out their nominating ballots.

True, the Academy may need reminding of Grand Budapest, which came out in late March. But Boyhood was released in mid-July, only a month and a half before Telluride. If Gray is right that it has already receded from the minds of Academy members, then the cluster of big festivals starting with Telluride forms a major cut-off point that downplays films released in the first eight months of the year. The Oscar-buzz coverage in the wake of the big August-September-October festivals tends to create the impression that the “awards season” is just beginning, and that the best-received films that premiere there and the ones that are released during the big holiday season are the ones that will be nominated. As Gray points out, all the best-picture nominees of 2013 were films released in the last three months of the year.

It would seem logical for the studios to be displeased at this effect. After all, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences is an organization founded and supported by the biggest Hollywood production/distribution companies. At least in recent decades, the main functions of the Oscars are to publicize films and to bring in a large sum of money for the television-broadcast rights. The latter supports the Academy’s other, less well-known activities, like lobbying and film preservation. Sure, Oscar buzz is great publicity for the few titles that receive it. But if eight months’ worth of worthy films are increasingly treated as inconsequential, that’s not good for business. So far, however, the Hollywood producers don’t seem to be doing much to remind Academy members of the older releases. So far the main tactic used to remind Academy members of older films is to hold special screenings with talent present for Q&As. Such events obviously reach only a small portion of the widely scattered membership.

Are there advantages for a big festival that avoids competition for likely award films? A report on the New York Film Festival in Variety, “NY Film Fest: Less Risk, More Reward for Studios,” suggests that there are:

From a distributor’s perspective, NYFF can sometimes be a smart choice since there are no awards, and coming later in the season, less chance for negative buzz to build on potentially divisive end-of-year releases. “It’s a safer but well-respected festival,” says one distribution exec. “It’s a good litmus test for a film, without the risk of everything blowing up in your face. If it plays well, you can put more into (marketing) it.”

The story’s author spoke with the festival’s director, Kent Jones, who plans to stick to a program based on quality films. He “stresses that while he’s not opposed to the occasional sale, there will be ‘no marketplace,’ and ‘business and curation won’t get mixed up.'” The piece concludes, “And if the fest wars continue to heat up, a less competitive NYFF just might end up as a more attractive option for filmmakers looking to stay out of the fray.”

Samuel Fuller, or Jean-Luc Godard, said that “Cinema is a battleground,” but I don’t see why film festivals should be.